Ethiopia: How Political Change Transforms Hydropolitics

Tezeta: a mode of music in Ethiopia, with this version recorded after the Ethiopian revolution of 1974. It relates to understanding 'the meeting of force and meaning', relating to nostalgia as the 'act of memory' and a profound sense of lot memories.

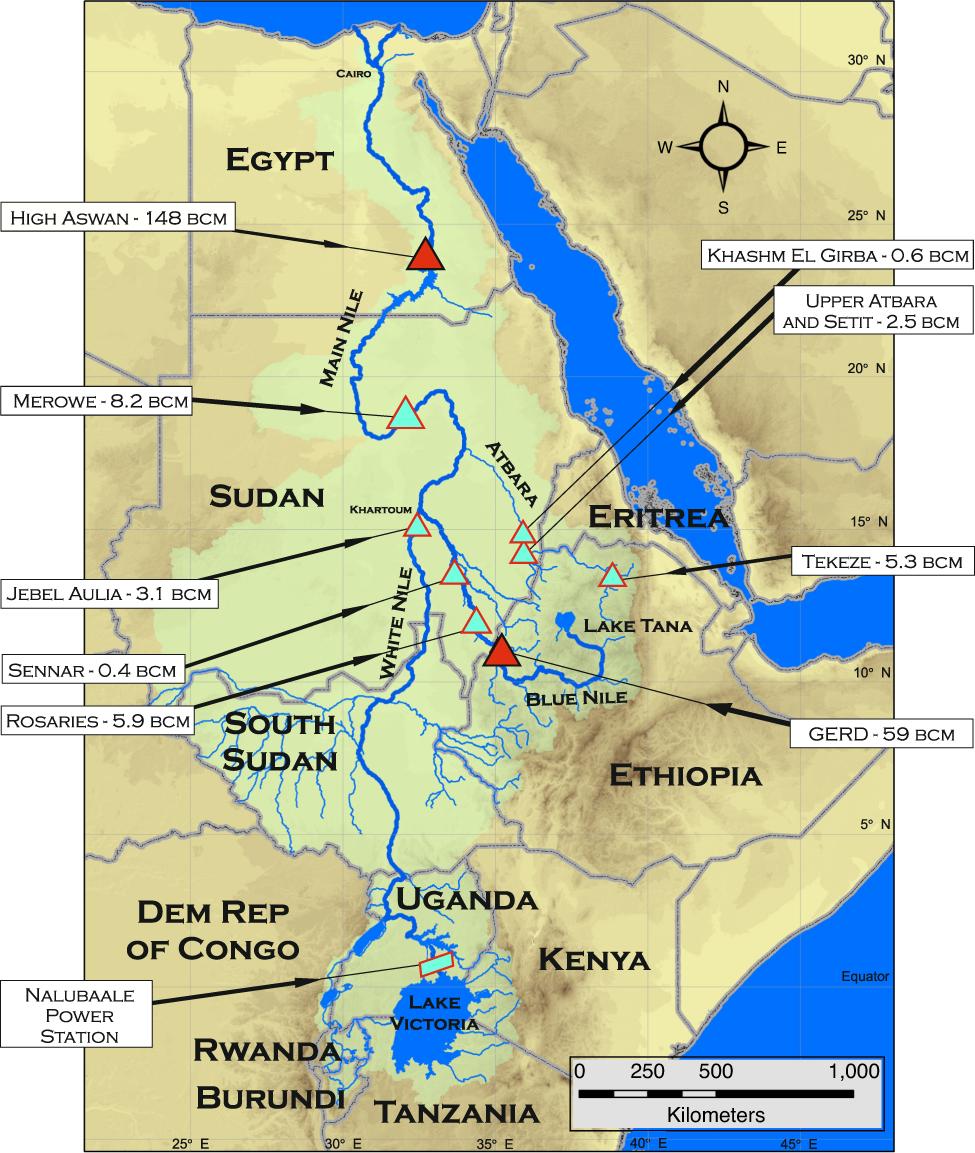

Despite being the source of 85% of the Nile's total waters, Ethiopia has not been viewed as a hegemonic riparian state along the Nile (Arsano and Tamrat 2005). 86% of the Nile's waters originates from the Ethiopian highlands, as Ethiopia virtually controls the most essential source of the Blue Nile, as well as many sources of the White Nile, as Figure 1 highlights (Kendie 1999).

(below) Figure 1. A hydrological map of the Nile River Basin, with indications of reservoir storage volumes along certain infrastructural features along the various waterways. It is important to indicate in the map, how not only the sources of the Blue Nile are incorporated within the Ethiopian highlands, but also how many tributaries of the White Nile stem from Ethiopia. This is crucial towards portraying the hydrological significance of Ethiopia within the Nile Basin (Wheeler et al. 2020)

Why is it that, despite Ethiopia being the source of most of the Nile's waters, that it has not been a leading player in Nile Basin water management? If anything, Ethiopia being the source of water has resulted in the hegemonic riparians of Egypt and Sudan being able to hold power over Ethiopia, in deciding the fate of their hydrology.

To answer this hypothesis, we must incorporate wider political contexts when analysing Ethiopian hydropolitics at any given period. During the time of writing of 'Tezeta' in the midst of revolution, conflict and famine, Ethiopia experienced limited hydrological development, particularly as it lacked the capital to do so. An increase and catalyst in development occurred during the period of changing political and economic contexts, with Zenawi's ministership acting as a continuum shift in national development, and subsequently hydrological development (Cascao 2009). During Zenawi's dichotomy of power, Ethiopia advanced towards a market economy, incorporating multilateral cooperation with global donors to not only stabilise the economy, but to invigorate growth further. An integral policy direction Ethiopia took was shifting hydrological management to international consultancy, to promote large-scale infrastructural programmes such as hydropower dams and irrigation schemes (Cascao 2009). Ethiopia has been able to utilise this aid to conduct hydrological development along the Blue Nile Basin. These actions have allowed Ethiopia to gain the capital to lead the continuum shift across the Nile Basin, towards a new dichotomy with more stable and equitable sharing of water resources and regional, multilateral cooperation. In one sense, Ethiopia as the spearheading riparian in hydrological development schemes as a form of mutually beneficial programmes has managed to achieve greater hydropolitical, almost hydro-hegemonic, power in the Nile Basin.

In one regard, we can assess the contrasts of prevailing legacies between hegemonies, as Egyto-Sudanese hegemony was typified by conflict to protect their 'divine right' to the Nile's waters, while Ethiopian hydro-hegemony managed to fit under a guise of multilateral cooperation, while also being largely self-beneficial (Cascao and Nicol 2016).

In the next post, we will look at how Ethiopia has managed to manipulate its newfound hydro-hegemony to pursue hydrological infrastructural developments, incorporating a wider share of Nile's water resources. Of course, when talking about Ethiopian hydrology, we have to talk about the GERD (Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam), but it is just as important to discuss the metaphorical small-print: the legislation that has allowed Ethiopia to pursue these programmes, and spearhead multilateral hydrological cooperation.

Comments

Post a Comment